|

Smart Growth: Presentation to Technologie, transports et modes de vie Palais du Luxembourg Paris 6 December 2001 By Wendell Cox, Wendell Cox Consultancy It is a pleasure to be here with

you today. I first of all want to express the gratitude of Americans for the

strong support France has provided after the tragic events of September 11.

Your president, Jacques Chirac was the first international leader to visit

our country after the attacks and was the first to visit the World Trade

Center site. Today I may say some things that

will be very surprising and may, in fact, be upsetting to some of you. There

is international concern about urban sprawl --- the tendency of our cities to

consume more land. There is no doubt that this is happening. But there is

serious question about the extent to which, if any, it is a problem. Much of

the data analysis I will present is based upon information from the recent

Jeffrey Kenworthy and Felix Laube volume on international cities and

transport from 1960 to 1990. A strong anti-sprawl movement

has emerged around the world. In the United States, the movement uses the

title “smart growth,’” and I intend to describe to you the problems with

smart growth today. The smart growth movement

largely holds that we need to make our urban areas more compact and dense, so

that less land is taken. In addition, smart growth seeks to significantly

increase public transport use, while discouraging both auto use and highway

construction. Principal smart growth strategies involve rationing ---

rationing of land through development bans in certain areas and urban growth

boundaries --- rationing development by larger per unit fees, ostensibly to

provide infrastructure. Two rationales for smart growth

are particularly erroneous. The first is that urban sprawl must be contained

to preserve valuable agricultural land. Indeed, agriculture has become much more

productive throughout the world, and we simply don’t need all the land that

was required for agricultural production before. Over the past 50 years,

urbanization in the United States has consumed less than one-fifth of the

land that has been taken out of agricultural production. The second erroneous

rationale is that urbanization is consuming open space. In fact, over the

last 50 years, 1.5 hectares of rural parks have been established for every

1.0 hectare of new urbanization (Figure).

If you followed the debate in

the United States, you would get the impression that urban sprawl and

suburbanization were exclusively American issue. I presume you know that our

American central cities have lost population, while suburban areas have grown

significantly. I presume that you also know that the same thing has happened

in European cities. Virtually all of the growth has been in the suburbs for

approximately 50 years. You can see this by considering

the population density losses of the Paris urban (developed) area compare to

that of Chicago. While Chicago started from a lower 1960 base, the rate of

density loss in the Paris area has been greater (Figure).

Of course, it is clear to all

that American cities are less dense than those in other parts of the world.

European urban areas are five times as dense as those in the United States

(Figure). But as I noted before, virtually all urban areas are sprawling to

lower densities.

There is a close relationship

between high density and high public transport market share. In Europe,

public transport market share is about 20 percent. This compares to less than

two percent in the United States (Figure). And if New York is excluded, the

figure is closer to one percent. In fact, New York is the most untypical of

American cities and resembles a European city more.

The smart growth advocates tell

us that urban sprawl has created traffic congestion, and that if we will just

impose their solutions, conditions will improve. Nothing could be further

from the truth. Traffic densities rise as population density rises. This is

clear from both the domestic US and international evidence. With its higher

population densities, Europe, with its higher urban densities, has double the

traffic densities of the United States (Figure).

It is, of course, true, that as

population densities rise, people tend to drive less. But the reduction in

per capita driving is not even close to that which would be required to

reduce overall traffic volumes. In the United States, traffic volumes tend to

increase from 0.8 to 0.9 percent for each 1.0 percent increase in density

(Figure).

But because higher traffic

intensity increases traffic congestion, average travel speeds are reduced.

This means that not only is there higher travel density, but there is a

higher density of vehicle hours. Further, the US evidence shows that air

pollution reduction is optimized between 55 and 90 kilometers per hour --- a

speed well above the average achieved in urban areas (Figure). The theory is

proven by the performance. Both nationally and internationally, higher

densities are associated with higher air pollution intensity.

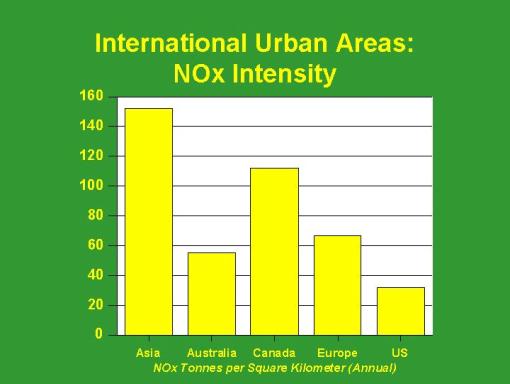

The NOx table is typical of the

comparative pollution densities of international cities (Figure).

Meanwhile, air pollution is going

away. We have seen driving increase approximately 30 percent since 1970. Yet,

air pollution has fallen, from 5 percent for NOx to more than 40 percent for

CO2 and 60 percent for VOCs (Figure).

Because traffic densities are

lower, and travel speeds are greater, cities that sprawl more tend to have

lower journey to work travel times, both domestically and internationally .

This is exactly the opposite of what is advertised by the smart growth lobby.

In the United States, the average automobile commute speed is more than 55

kph. The average public transport commute speed is approximately 22 kph. This

means that people who have cars have access to five times as much

geographical area in which to travel and work.

Then there is the matter of

public transport. Public transport is very effective in certain markets.

Public transport provides a valuable service in highly dense core cities and

to employment in the cores of such cities. Indeed, it is hard to imagine a

much more effective public transport system that RATP provides with buses and

the metro in the ville de Paris. But the suburbs are another matter. This is illustrated by Portland,

Oregon, our leading ecological city. Portland has adopted all manner of smart

growth policies, including a highly restrictive urban growth boundary and

substantial increases in public transport service. Yet, even in Portland, few

people can get to their jobs on public transport that is automobile

competitive outside downtown. Public Transport provides reasonably time

competitive service to the central business district, from 78 percent of

residences in the urban area. But less than 15 percent of the metropolitan

area’s jobs are in the central business district. The other 85 percent have

little, if any transit service. Our survey of 100 Portland suburban locations

leads to a conclusions that, on average, fewer than five percent of residents

can reach a particular suburban work location on public transport that is

time competitive (Figure). That means, quite simply that people will not ride

public transport, because they will not take trips of 90 minutes or more that

can be accomplished in 20 to 40 minutes by car.

Which bring us back to Paris ---

that ultimate city of western civilization. No urban area has a more dense

core. No city is more walkable or public transport oriented. Portland is

surely not Paris. Indeed, Paris is not Paris. The

city that we associate with Paris is only a small core of a much larger urban

area. Approximately 80 percent of the people in the Paris area live outside

the ville de Paris. Approximately 85 percent of the employment is outside the

core. Generally, time competitive public transport service is not provided

from suburban residential locations to suburban work locations. There is no

doubt that the public transport system effectively serves the central city,

and also provides effective service to the central city from the suburbs on RER.

But in this ultimate of western cities, public transport simply does not

provide time competitive mobility in the suburbs. You are not going to force the

millions of Americans who live in the suburbs into the city. Neither are you

going to force 8 million Parisians into the city from the suburbs. Whatever we do in the central

city it is time to recognize that there are not the financial resources to

provide the comprehensive time competitive public transport services

that would be required to effectively

serve suburb to suburb markets. In many cities, suburb to suburb markets are

commanding virtually all of the growth. But there is more. American

anti-sprawl activists like to claim that low income households are disproportionately

harmed by sprawl. And, while sprawl tends to increase transport expenditures,

it lowers others. The cost of living is generally lower in more sprawling

urban areas (Figure). This is probably also true in Europe, where higher

distribution costs due to slower operating speeds and higher labor costs

generally tend to be associated with more dense areas.

Which brings me to perhaps the

most important point --- that smart growth increases social inequity. The

American dream of home ownership has achieved an record household rate of 70

percent in recent years. Yet, as you know, America has less affluent

minorities, especially African Americans (blacks) and Hispanics. Their home

ownership rates remain in the 45 percent to 50 percent range, well below that

of non-Hispanic whites. But in recent years there has been progress, and

minority home ownership has risen at a faster rate than that of non-Hispanic

whites. But as anyone with the most

remote acquaintance with economics knows, when you ration a scarce good, the

price goes up. So as the smart growth advocates implement their urban growth

boundaries, they ration land and drive the price up, not only of land but of

other factors of housing production, since their rationing also reduces

competition in the home building and development industry. The effect can be

seen in eco-friendly Portland, where housing affordability has dropped by far

the most of any major urban area in the last decade (Figure). Portland

apologists have tried to claim that Portland’s strong population growth is

responsible for the rising prices, but that does not explain why Phoenix and

Atlanta, with much stronger growth, experienced improvements in affordability

over the same period. In the San Francisco Bay area, planners are rationing

housing development through very large development impact fees, which are the

same rate regardless of the value of house being constructed. This has been a

significant contributing factor to San Francisco’s high cost housing market,

which is the nation’s least affordable.

And so the anti-sprawl movement

and smart growth does not deliver on its promises. There is more traffic,

more time in traffic, more pollution, higher cost and more social exclusion.

This is not to support urban sprawl, it is rather to support development

wherein urban planners interfere with market forces to a minimum. A year or so ago, a number of us

of like mind met in the Rocky Mountains and adopted the :”Lone Mountain Compact,”

which set out principles of market based development. The key philosophical

underpinning of that statement is that (Figure): …absent

a material threat to others or the community, people should be allowed to

live and work how and where they like. Such a view is consistent with

the philosophies of our two nations, that have faced so many challenges

through the years to preserve liberty.

|